|

Where are the citizens?

Where are the youth of Europe? Where is their voice? Aren’t they the first who could save Europe ‘from that stagnating pool of abstinence and acquiescence?’

A contemporary cri du coeur?

No, these words were spoken already more than half a century ago, by a 23 year-old-princess, who, without the slightest reservation, typified Europe as a giant on feet of clay: a beautiful ideal but without any real substance.

In September 1961 the Dutch crown princess Beatrix addressed some four hundred young students and recent graduates in Toulouse, gathered from all over Europe. The fine-sounding phrases on European unity had to be transformed into action, she felt. ‘Apathy is an offence!’

To just think and talk would not suffice; it would be crucial to act.

Don’t ask what Europe might do for you, but what you might do for Europe.

The princely speech resulted in the foundation of the European Working Group, with Beatrix as its inspiring president, to the horror of the Dutch government in general and its foreign office in particular. That the Working Group envisaged a Europe extending beyond the iron curtain caused

Don’t ask what Europe might do for you,

but what you might do for Europe

considerable fear that the crown princess would expose herself to that tricky ‘Third Way’,

the misleading ‘neutral’ track in between the Atlantic Alliance and the Eastern bloc.The working group’s desire to engage in joint European projects in underdeveloped countries, in line with its creed ‘to think manually’ was not what the government wanted to hear either. Development work would have to be subservient to Dutch foreign policy. Private initiatives, it was felt in those days, had to be suppressed as much as possible. A ‘peace corps’ along the lines of President Kennedy’s American initiative should be a government venture and certainly not a ‘European’ one.

The Dutch Foreign Office’s attempts to fit the crown princess within its own strategies and policies failed sadly. The Group went its own way and achieved much repute through the reconstruction of Dousadj, an Iranian village that had been wiped out by the earthquake of 1962. National groups were established in several European countries, with a particularly strong presence in the Netherlands, Great Britain and Norway, while European voluntary development work was undertaken in Asia, Africa and Europe itself. New ideas and practices on ‘development from below’ gained acclaim. Finance, however, remained the major constraint.

In 1967, five years after the European Working Group had come into being, beer magnate Freddy Heineken took the initiative to compose a powerful and financially strong Board of Trustees. Nine captains of industry collaborated in this venture, significantly attracted by the Group’s royal backing. What drove them was standing, rather than Beatrix’s ideals and activities.

In 1968 the trustees made their final contribution with the explicit condition that it be used for the discontinuance of the European Working Group. The ongoing projects, in Iran, India and Africa, were transferred to Oxfam and the United Nations Association of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. Yet the work that had been done and the outward looking European flair that drove the founders created lifelong bonds. The core members still hold their reunions, reflecting upon a future that never was.

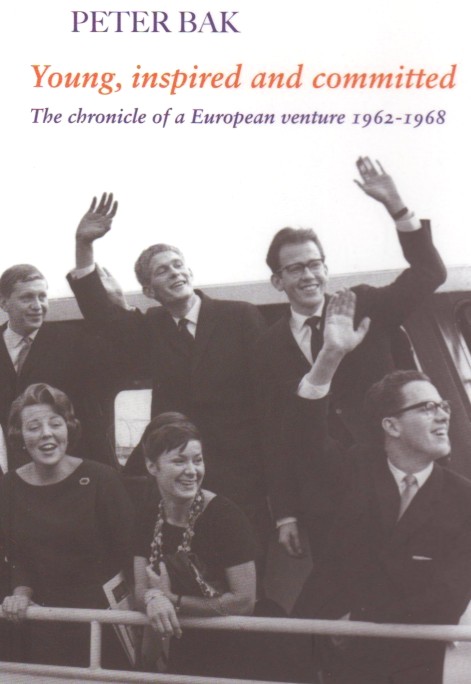

> Presentatie op University College London

> Nederlandse editie